-

-

Modos de Condenar Certezas, por JOSÉ BECHARA

CLIQUE PARA ASSITIR O VIDEO / CLICK TO WATCH THE VIDEO -

PRESS RELEASE

Planejada para inaugurar em março de 2020, a exposição Modos de Condenar Certezas do artista carioca José Bechara já estava pronta quando teve que ser suspensa devido à quarentena imposta pela pandemia do Covid-19. Com a extensão do período de quarentena, decidimos nos lançar no desafio de exibi-la virtualmente, mostrando imagens, vistas da exposição, vídeo com locução do próprio artista e texto crítico de Clarissa Diniz.

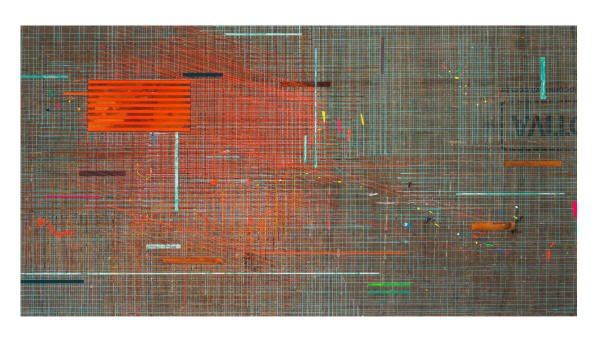

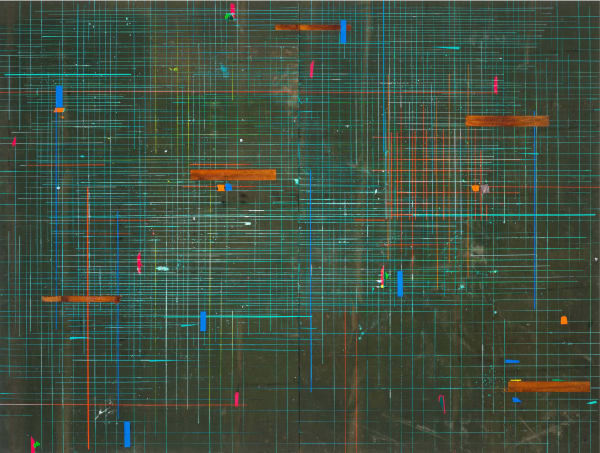

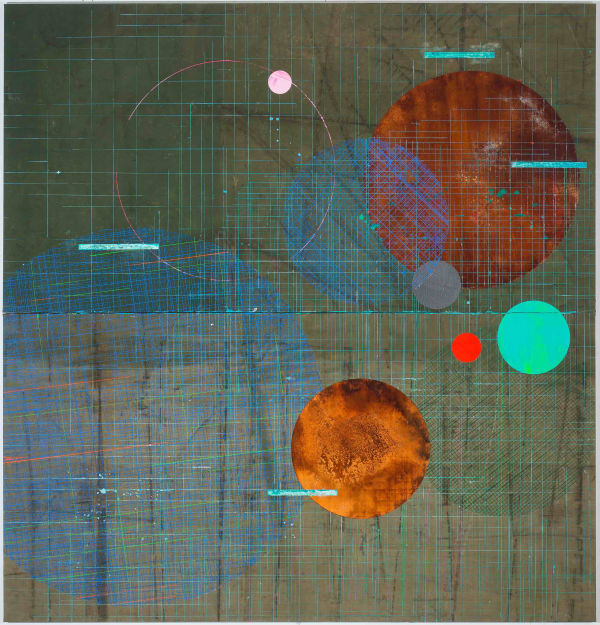

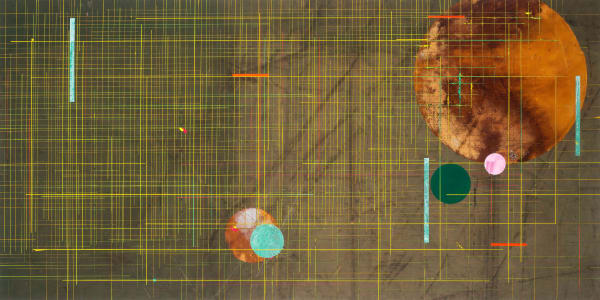

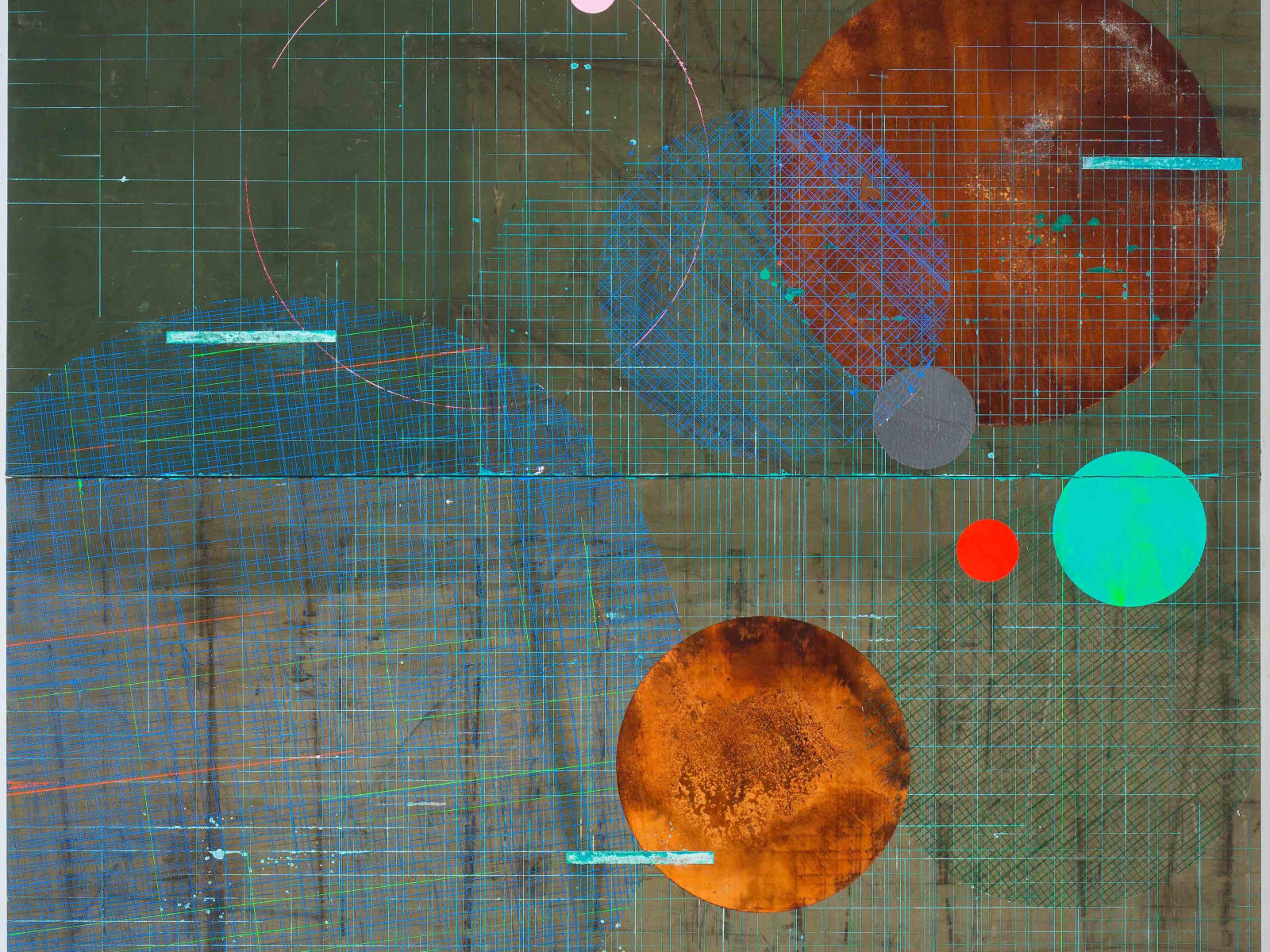

APRESENTAMOS aqui 11 obras recentes, dentre pinturas de grande formato e esculturas, Com uma pesquisa cromática mais luminosa, ONDE o artista constrói espaços geométricos que se deslocam entre rigor formal e ocorrências randômicas.

Se aprofundando em seu caráter experimental e na utilização diversificada de métodos e materiais, o artista permite novas experiências no campo pictórico, revelando tons e tramas, trazendo espaços elaborados a partir de campos que oscilam entre fronteiras para revelar uma construção que se esforça para emergir no plano.

A exposição reúne um conjunto de pinturas nas quais a tradição geométrica, que usualmente afirma um mundo ideal, cede lugar a uma crise de certezas e elogia as imperfeições desse mesmo mundo constituído por dúvidas, receios e falhas, reflexo da atualidade, que se move oscilante, colidindo em seus arranjos sociais.

-

obras sala 1 / works room 1

-

-

Obras sala 2 / Works at room 2

-

A DÍVIDA ETERNA DE JOSÉ BECHARA

TEXTO DE CLARISSA DINIZ PARA A EXPOSIÇÃO, 2020Que parte significativa das pinturas de José Bechara advêm de uma relação de troca é um dado bastante conhecido. Proponho, todavia, que dediquemos alguns parágrafos à dívida que o artista adquire ao trocar, com caminhoneiros, lonas novas por aquelas que estavam em uso – as quais, repletas de vestígios do tempo e do trabalho implicados no transporte, se tornam os territórios da obra.

Ainda que seja possível fazê-lo, a este texto não interessa a dívida economicamente circunscrita à mais-valia produzida sobre a lona enquanto elemento do caminhão e a outra versão do mesmo material – a obra –, gestada ao sofrer a ação do artista e ser inscrita no campo da arte: assimetria financeira produzida e gozada entre dois estados de um único – apesar de transformado – corpo[1]. Reconhecer esse débito (que, ademais, atravessa a história da arte euroetnocêntrica, podendo ser entrevisto em práticas de apropriação tão distintas quanto os ready-mades ou os imaginários elaborados pelos artistas viajantes em seu rotineiro tráfico simbólico) é o ponto de partida sociopolítico para, aqui, pensar brevemente sobre os modos de sua realização formal.

É o próprio José Bechara que, como se depreende de suas entrevistas, nos adverte de que sua obra “está sempre atenta aos acidentes”: “alguma coisa cai, alguma coisa falha, alguma coisa falta..., e esse tipo de problema é o problema que, na verdade, dá fôlego e animação para perseguir, para fazer o próximo trabalho”. Para o artista, embora sua pesquisa possa ser compreendida a partir da chave da “abstração geométrica” (e, mais especificamente, do vocabulário construtivo), seu interesse não está na “afirmação de um mundo” através de um “instrumento de cálculo”. A geometria de sua obra é, por isso, “imprecisa”: “essas linhas, embora estejam aqui, estão numa condição de aparecimento e desaparecimento. (...) A geometria falha como falhamos, é imperfeita como somos imperfeitos, e deve produzir tremendos esforços para emergir, para existir. A vida é assim”.

Numa crítica à racionalidade moderna ocidental que – em campos tão contíguos quanto o da arte, da ciência ou da política – tudo anseia separar, organizar e determinar, José Bechara enfatiza seu elogio ao acidente em razão de sua imprevisibilidade e, consequentemente, pela capacidade de desafiar o poder centralizado da “toda poderosa” mão do artista. Nesse sentido, afirma que sua obra é “uma intenção em condições de ser afetada pelos acidentes”, a partir dos quais se dá “uma aventura mental pra organizar as próximas ações (...) na direção de se chegar a uma coisa” [2].

*

Tornar-se disponível aos acidentes tem se dado, há mais de duas décadas, como um processo de experimentação que depende principalmente de duas presenças/fenômenos oscilantes: as lonas advindas dos caminhões e as oxidações que o artista produz sobre elas. Da combinação entre a superfície marcada das lonas e os efeitos da oxidação do cobre ou do ferro jorrados sobre as mesmas emergem as linhas, a cor, a espacialidade e a densidade de suas pinturas; organizadas, interferidas e tornadas mais ou menos visíveis a partir dos gestos de José Bechara.

Essa materialidade – devedora da plasticidade da lona e da oxidação – se constitui, portanto, através do tempo: do período de uso da lona à oxidação que, nas palavras de Bechara, se dá num processo de “indução e espera”[3]. Ao invés de pretensamente criadas pelo artista, a distribuição das manchas e os tons acinzentados que constituem a atmosfera cromática das pinturas advêm das lonas, bem como suas cores alaranjadas e azul-esverdeadas emergem das propriedades dos metais ali oxidados. O espectro de cores que, ao longo dos anos, foi tornando-se característica da obra de Bechara é, fundamentalmente, uma criação conjunta – inscrita no espaço-tempo distribuído entre os caminhões e os caminhoneiros, a chuva e o sol, a lona e seus recortes, o tempo, os metais, a umidade, as tintas, as fitas adesivas, a gravidade, as intenções e os acidentes, dentre outros – na qual é evidente que a agência não é exclusiva ao artista, nem restrita a algum dos elementos implicados no surgimento dessas pinturas, senão dispersa ao longo de sequências não-lineares de acontecimentos sociais, fisicoquímicos e estéticos.

Sob o impacto visual e espacial dessas obras – cuja escala ampliada e “padronagens” cromogeométricas saltam aos olhos por haverem sido elaboradas na condição de protagonistas das pinturas – camufla-se um sistema silencioso, lento e por vezes invisível de composição que, como confessa Bechara, revela seu interesse “na forma sim, mas desde que a pesquisa tenha uma relação com qualquer drama humano”[4].

A estridência estética de suas obras, por ser devedora de forças diversas, nos faz ver o quão cínica pode ser a ambição de soberania que ética e politicamente sustenta a ideia de autonomia da forma ou da obra de arte.

O “drama humano” ou, como Bechara também gosta de dizer, a “dimensão existencial”[5] de sua pesquisa reside, assim, menos em eventuais metáforas que a geometria ou alguma de suas características formais possam inspirar, mas, sobremaneira, numa economia do poder entre as matérias e as agências implicadas na gestação das pinturas – um sistema que, do início ao fim, situa o artista na posição de devedor. Em débito não somente por conta da apropriação originária da lona como também em razão de todos os “acidentes” que são, como ele nos adverte, corresponsáveis pela obra.

*

De formação católica, não é raro escutar o artista referir-se à suposta assimetria entre os seres humanos e Deus. Numa conversa, Bechara comentou que passou muitos anos intrigado com a condição de que, herdeiros de um pecado original, viveríamos em torno dessa dívida impagável que sustenta, por sua vez, o gap epistemológico a partir da qual erige-se uma política de representação na qual Deus figura hierárquica, moral e cosmologicamente distante e mais elevado do que nós. A separação entre nós e Ele e, por outro lado, a missiva de que seríamos ou deveríamos ser à Sua imagem e semelhança angustiava Bechara filosoficamente, até o momento em que, invertendo os polos da relação, convenceu a si mesmo da reversibilidade dessa mandatória: “ora, se somos à imagem e semelhança Dele, Ele é à nossa imagem e semelhança”[6], concluiu.

A interpretação de Bechara simetriza os termos equacionados de um dos fundamentos do catolicismo ao entender que também Deus estaria em débito conosco, produzindo uma economia cuja complexidade inviabiliza saber ao certo quem é devedor e quem é credor. Devendo uns aos outros a referência (ou o capital) que nos configura como humanos ou divindades, estamos implicados num território de infindáveis relações: inseparáveis, indeterminadas, insurgentes. Destituídos de qualquer autonomia, nem nós, nem Ele – nem o sujeito, nem a forma – são, para Bechara, circunscritos em seus próprios termos, perspectiva a partir da qual se dão os interesses de sua obra: “Nem [o] espaço caótico [da visualidade da lona], nem [o] formalismo [da grade construtiva que faço sobre ela] me interessam, mas o que resulta desse confronto, que é um espaço constituído pela existência simultânea desses dois acontecimentos. É uma equação entre esses termos”[7].

*

A dívida, essa velha conhecida do capitalismo, é também especialmente familiar para nós, ex-colônias (sic), dado o fato de que sua ficcionalização inventou um sistema econômico, político, religioso, policial, discursivo, cognitivo, moral, cultural – e estético – que nos subalternizou, fazendo com que, por meio do trabalho escravizado, tivéssemos que sanar a dívida que nos foi atribuída por um aparato de força e de violência de todas as ordens. Transformando-nos em devedores, o discurso e a economia da dívida elaboraram uma cínica racionalidade para o inegável fato de que, com a invasão e a expropriação colonial, passávamos a ser os grandes credores do mundo – fonte de recursos naturais, humanos e simbólicos; partícipes e protagonistas de uma nascente “economia global”.

Nesse contexto, pensar nos termos da dívida não é exatamente aderir à sua dimensão capitalista nem propor uma leitura economicista, mas sublinhar os interesses éticos e políticos de sua reiterada neutralização enquanto operadora de nossas ações e obras. Ignorar o quão somos devedores para, assim, produzir narrativas estéticas nas quais figuramos como um duplo de Deus em sua versão Toda-poderosa – reencenando, com nossas intenções, gestos e projetos, uma espécie de eterno big bang – parece desviar-nos da peremptória necessidade de nos educarmos para criarmos a partir das implicações de todas as forças do mundo, e não em detrimento ou a reboque delas.

José Bechara aponta nessa direção quando se dedica a sistemas de cocriação nos quais agem forças tão distintas quanto o próprio artista, as lonas e a oxidação, dentre incontáveis acidentes: “Ter dado certo é também um acidente. Todo acidente é bom. Eu lido com ele; eu conto com ele”[8]. Dissonante em relação aos parâmetros purificantes (“pureza é desonestidade”[9], dispara) de certa abordagem – costumeiramente construtiva, quase sempre geométrica – da forma, mas ao mesmo tempo filiado a ela por circunstâncias históricas e escolhas estéticas, a obra de Bechara situa-se a meio caminho entre a tradição formalista e a disposição a afetar-se com forças oriundas de outros territórios.

De alguma forma, é porque estão sob o peso dessas dívidas que as formas de José Bechara fazem “tremendos esforços para emergir, para existir”. Implicadas numa complexa e indestrinchável trama de débitos e créditos entre fenômenos e existências sociais, fisicoquímicas e estéticas, suas pinturas retroalimentam essa singular economia da arte, preferindo, ao seu habitual desejo de alforria ontológica, a dívida eterna.

[1] “A ação é a seguinte: pego uma lona novinha, limpa, sem nenhuma marca a não ser a logo do fabricante. Ela é laranja. Quando dou essa lona para o caminhoneiro, entrego uma matéria necessária para ele e desnecessária para mim, para obter aquilo que já não serve para ele, mas serve a mim, em uma outra paisagem. Não é mais a das estradas, vai para um outro lugar. O trabalho começa no posto de gasolina, na cooperativa de caminhoneiros”.

José Bechara em entrevista com Glória Ferreira. Quando a noite encosta na janela, 2007. Disponível em: http://josebechara.com/quando-a-noite-encosta-na-janela/.

[2] Depoimentos do artista no vídeo José Bechara – Visto de frente é infinito. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMNtG0bv-2c.

[3] Depoimento do artista em conversa com a autora.

[4] José Bechara em entrevista com Glória Ferreira. Quando a noite encosta na janela, 2007. Disponível em: http://josebechara.com/quando-a-noite-encosta-na-janela/.

[5] Depoimento do artista em conversa com a autora.

[6] Depoimento do artista em conversa com a autora.

[7] José Bechara em entrevista com Glória Ferreira. Quando a noite encosta na janela, 2007. Disponível em: http://josebechara.com/quando-a-noite-encosta-na-janela/.

[8] Depoimento do artista no vídeo José Bechara – Visto de frente é infinito. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMNtG0bv-2c.

[9] Depoimento do artista em conversa com a autora.

-

THE ETERNAL DEBT OF JOSÉ BECHARA

TEXT BY CLARISSA DINIZ FOR THE EXHIBITION, 2020It is widely known that a significant part of the paintings by José Bechara come from a relationship of exchange. However, I propose we dedicate some paragraphs to the debt the artist acquires when exchanging new tarpaulins with truckdrivers for used ones –replete with the marks of time and usage from the transport industry –, which become the territories of his works.

Even if it were possible, this text is uninterested in the economically circumscribed debt of the greater value created from the tarpaulin as an element of the truck and the other version of the same material – the art work – born from being subjected to the artist’s action and being enrolled into the art world; a financial asymmetry produced and relished between two states of a single, albeit transformed, object[1].

Recognizing this debt (which, furthermore, crosses the history of euro-ethnocentric art and can be glimpsed in such distinct appropriation practices as in the ready-mades or imagined objects developed by travelling artists in their routine symbolic traffic) is the sociopolitical starting point from which to briefly consider the methods of its formal realization.

It is José Bechara himself who, as can be gleaned from his interviews, warns us that his work is “always paying attention to accidents”: “something falls, something fails, something else is missing… and this kind of problem is the problem that, in fact, gives you the strength and interest to follow, to make your next piece”. For the artist, although his research can be understood based on the key of “geometric abstraction” (and, more specifically, of a constructive vocabulary), his interest is not in the “affirmation of a world” through a “calculating instrument”. The geometry of his work is, therefore, “imprecise”: “these lines, despite being here, are in a condition of appearing and disappearing. (…) Geometry fails like we fail, it is imperfect like we are imperfect and great amounts of effort are required to make it emerge, to exist. Life is like that”.

In a critique of modern Western rationality where – in fields as contiguous as those of art, science or politics – everything is anxious to separate, organize and identify, José Bechara emphasizes his praise of the accidental due to its unpredictability and, consequently, its capacity to challenge the centralized power of the artist’s “all powerful” hand. In this sense, he states that his work is “an intent in conditions of being affected by accidents”, based on which arises “a mental adventure to organize the next actions (…) in the direction of arriving at a thing” [2].

*

Becoming available to accidents has become, over more than two decades, like a process of experimentation that mainly depends on two, oscillating presences/phenomena: the tarpaulins from trucks and the oxidations that the artist produces on them. From the combination of the tarpaulins’ pocked surfaces and the effects of the copper or iron oxidations strewn over them, what emerge are the lines, color, spatiality and density of his images; organized, interfered and made more or less visible by the gestures of José Bechara.

This materiality – in debt to the tarpaulin’s and oxidation’s plasticity – is, therefore, arrived at through time: from the period during which the tarpaulin is first used to the oxidation that, in Bechara’s words, happen over a process of “induction and waiting”[3]. Instead of being supposedly created by the artist, the distribution of the stains and grey tones that make up the chromatic atmosphere of the images comes from the tarpaulins, much like their orange and green-blue hues arise from the properties of the metals that have been oxidized. The spectrum of colors that, over the years, have become characteristic of Bechara’s production is, fundamentally, a joint creation – inscribed on the space time distributed over the trucks and truck drivers, the rain and sun, the tarpaulin and its cuttings, the weather, the metals, the humidity, the paints, the packing tape, gravity, intentions and accidents, among others – in which it is clear that the agency is not exclusively that of the artist, nor is it restricted to some of the elements implied in the creation of these images, unless dispersed over the non-linear sequence of social, physical, chemical and aesthetic events.

Under the visual and spatial impact of these pieces – whose expanded scale and “standardages” of color and geometry leap to the eye because they were made in the condition of being the protagonists of the images – there is a slow, silent system of composition that is camouflaged and, at times, invisible, but which, as Bechara admits, reveals the artist’s interest in “form, yes, but as long as the research has a relationship with some human drama”[4]. The aesthetic stridency of his pieces, owing to diverse forces, makes us see how cynical the ambition of self-determination is that ethically and politically sustains the notion of autonomy of form or of the work of art.

The “human drama” or, as Bechara also likes to say, the “existential dimension”[5] of his studies thus resides less in eventual metaphors that the geometry or some other of its characteristics can inspire, but, above all, in an economy of power between the materials and agencies implied in the creation of the images – a system that, from start to finish, places the artist in the condition of being indebted. Indebted not only because of the originating appropriation of the tarpaulin, but also due to all the “accidents” that are, as he tells us, co-responsible for the work.

*

Coming from a Catholic upbringing, it is not rare to hear the artist refer to the supposed asymmetry between human beings and God. In a conversation, Bechara mentioned that he had spent many years intrigued by the condition in which, as heirs of the original sin, we live twisted around this unpayable debt that, in turn, sustains the epistemological gap from which a policy of representation emerges and in which God is the hierarchically, morally and cosmologically distant and higher figure than us. The separation between us and Him and, on the other hand, the missive that we would or should be in His image and likeness, would leave Bechara in philosophical despair, until the moment in which, inverting the poles of the relationship, he convinced himself of the reversibility of this imperative: “well, if we are His image and likeness, He is our image and likeness”[6], he concluded.

Bechara’s interpretation balances the terms relating to one of the foundations of Catholicism by understanding that God is also indebted to us, producing an economy whose complexity makes it unfeasible to know for sure who is the debtor and who is the creditor. Owing to each other the reference (or capital) that makes us human or divine, we are implicated in a territory of undefinable relationships: inseparable, undetermined, insurgent. Made destitute of any autonomy, neither us nor Him – neither the subject nor the form – are, to Bechara, circumscribed in their own terms, the point of view from which the interests of his work arise: “Neither [the] chaotic space [of the tarpaulin’s visuality], nor [the] formalism [of the constructive grid he creates on it] interest me, but what results from this conflict, which is a space created by the simultaneous existence of these two events. It is a balance between these terms”[7].

*

The debt, this ancient debt known by capitalism, is also especially familiar to us, ex-colonials (sic), given the fact that its fictionalization invented an economic, political, religious, police, discursive, cognitive, moral, cultural – and aesthetic – system that has subordinated us, ensuring that, through slave labor, we have had to pay the debt attributed to us by an apparatus of power and violence of every magnitude. Transforming us into debtors, the discourse and the economy of debt have elaborated a cynical rationality for the inevitable fact that, with colonial invasion and expropriation, we became the great creditors of the world – the source of natural, human and symbolic resources; participants and protagonists of a nascent “global economy”.

In this context, thinking in terms of debt is not exactly adhering to its capitalist dimension or proposing an economic reading, but, rather, it underlines the ethical and political interests of its reiterated neutralization while operating our actions and works. Ignoring how much we owe to thusly produce aesthetic narratives in which we figure as a duo of God in his Almighty version – reenacting, with our intentions, gestures and projects, a kind of eternal Big Bang – seems to divert us from the decisive need to educate ourselves in order to create based on the implications of all the forces in the world and not in detriment or denial of them.

José Bechara points to this direction when he dedicates himself to systems of co-creation in which forces as distinct as the artist himself, the tarpaulins and oxidation, in addition to innumerous accidents: “It having worked out is also an accident. Every accident is good. I deal with it; I count on it”[8]. Dissonant in relation to the purifying parameters (“purity is dishonesty”[9], he challenges) of a certain approach – normally the constructive, almost always geometric – of form, but at the same time, affiliated to it by historical circumstances and aesthetic choices, the work of Bechara places itself half-way between formalist tradition and the willingness to affect itself with forces coming from other territories.

In some way, it is because they are under the weight of these debts that José Bechara’s forms make, “tremendous efforts to emerge, to exist”. Implicated in a complex and inseparable web of debts and credits between social, physical, chemical and aesthetic phenomena and existences, his images feed back into this singular economy of art, preferring, instead of its habitual desire for ontological manumission, eternal debt.

[1] “The action is as follows: I take a new, clean tarpaulin free of any markings except for the manufacturer’s brand. It is orange. When I give this tarpaulin to the truck driver, I am handing over an item that he needs and that I do not, in order to obtain that which is no longer of use to him, but is to me, in a different landscape. It is no longer of the roads, it goes to a different place. The work begins at a gas station, at the truck drivers’ co-op”.

José Bechara, from an interview by Glória Ferreira. Quando a noite encosta na janela, 2007. Available at: http://josebechara.com/quando-a-noite-encosta-na-janela/.

[2] Artist’s words, from José Bechara – Visto de frente é infinito. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMNtG0bv-2c.

[3] Artist’s words, from a conversation with the author.

[4] José Bechara, in an interview by Glória Ferreira. Quando a noite encosta na janela, 2007. Available at: http://josebechara.com/quando-a-noite-encosta-na-janela/.

[5] Artist’s words, from a conversation with the author.

[6] Artist’s words, from a conversation with the author.

[7] José Bechara, in an interview by Glória Ferreira. Quando a noite encosta na janela, 2007. Available at: http://josebechara.com/quando-a-noite-encosta-na-janela/.

[8] Artist’s words from José Bechara – Visto de frente é infinito. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMNtG0bv-2c.

[9] Artist’s words, from a conversation with the author.

-

CONTATO / CONTACT

GALERIA MARILIA RAZUK

contato@galeriamariliarazuk.com.br

tel: + 55 11 3079.0853

WhatsApp: +55 11 96082-3111

WWW.GALERIAMARILIARAZUK.COM.BR

RUA JERONIMO DA VEIGA, 131 - ITAIM BIBI - SAO PAULO - SP - BRASIL CEP 04536-000

JOSÉ BECHARA: MODOS DE CONDENAR CERTEZAS (WAYS OF CONDEMNING CERTAINTIES)

Past viewing_room